Impossibly complex, ruthlessly simple: the limitations and purpose of newsgames

Newsgames do a lot to educate audiences about important issues, from climate change to transport logistics, but by design they cannot tell the whole story.

A 1:1 model of something is the thing itself. As models shrink in size, detail and information get lost. Eventually they are only vague approximations of the original thing. A ship in a bottle can never tell the story of the real vessel it replicates on its own, cannot communicate its heft, or what it felt like to stand on its prow.

In Iain M. Banks’ wonderful Culture novel The Player of Games, the protagonist is invited to play in a tournament of the game Azad. The game shares its name with the empire that invented it: as the story progresses it becomes explicit that the game is essentially a 1:1 recreation of the Empire, from its politics and arts to its sanitation and waste systems. The winner of the tournament is the Emperor, having demonstrated their aptitude for statesmanship through the game.

Of course, in real life, no game comes close to that level of fine detail. The closest I can think of is The Campaign for North Africa (The Desert War, 1940–43). As you might expect from its name, this colossal board game is estimated to take around 1,500 hours to complete on average, and has levels of granularity that border on mania. The most commonly cited example is that the commander of the Italian troops has to source more water per turn, because the Italian army requires that water to make pasta.

In reality however that is a single consideration among many thousands. Here, for instance, are three separate steps a player must take on their turn, solely to do with water:

Calculate spillage/evaporation of water and adjust all supply dumps

Determine weather (tot weather = more evaporation of water)

Distribute water

Calculate attrition of units short of water and stores

Now multiply those considerations by everything from food rations to fuel, before you’ve even moved a piece on the 3 metre long board. You can invest points in researching gas caps for your vehicles! It is the most complicated war game of all time – and it still comes nowhere near being a 1:1 recreation.

Newsgaming

Since the early days of internet 1.0 journalists have sought to use games to educate people about complex issues. I remember playing – over and again – a game about helicopter rescue on the computer in my school’s library.

Since then, gamification has become an important part of storytelling around appropriate stories. When the Ever Given wedged itself into the silt of the Suez Canal, there were a glut of satirical games released that put you in the shoes of the captain of a container ship navigating the waterway. CNN, however, took a slightly more sophisticated tone with their newsgame dedicated to the incident – even though graphically it looks more like a container ship for ants than a true depiction.

Those are relatively straightforward games, based around an easy-to-understand real-world challenge. The lesson audiences are likely to take away is that it is difficult, without training, to drive a huge great dirty boat up a narrow channel.

But what about when journalists – or developers in general – want to communicate something closer to Azad with a newsgame? That’s where the diminishing information levels begin to bite, and force smart developers to come up with ways to pare back detail in favour of meaningful abstraction.

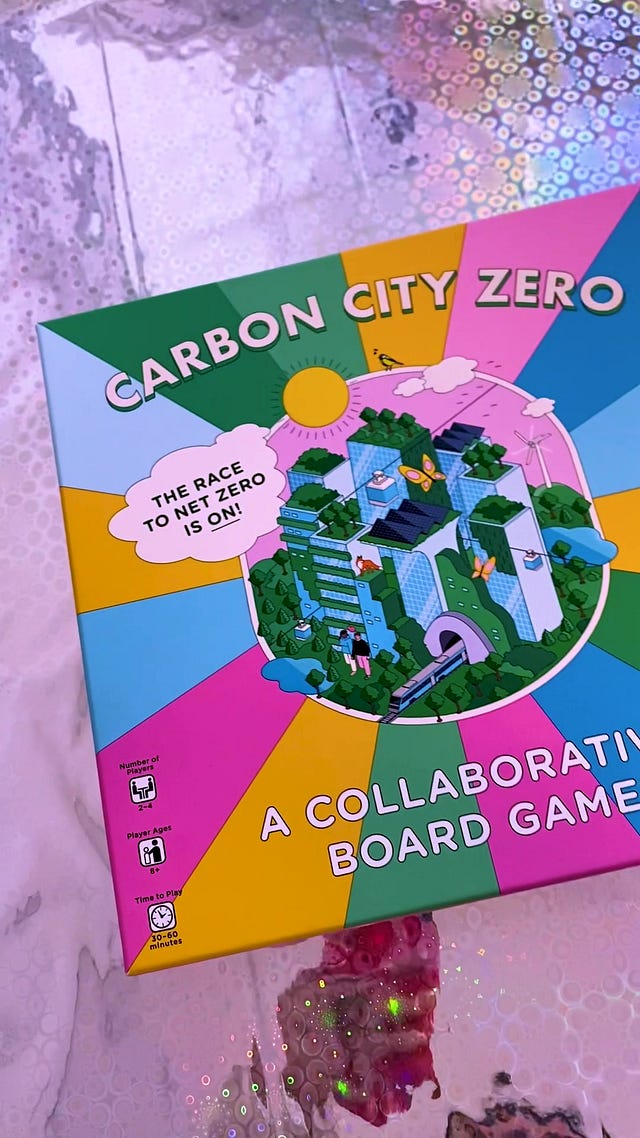

Take climate change, for example. It is a common cause célèbre for newsgame developers, as it has instant recognition as an issue and a number of well understood causes. More, because it is something right-minded people are keen to mitigate, there are easy goals and end-states that developers can include. That might be why it translates so well to tabletop, too.

In 2022 the Financial Times published a newsgame to coincide with Earth Day, titled ‘Can you reach net zero by 2050?’ At the time I wrote it was “a genuinely fun (and tricky) way of illustrating the multifaceted problems that come from transitioning from where we are now to Net Zero. With a limited number of ‘effort points’, where do you invest your pool of resources to ensure that Net Zero is achieved? It’s not a perfect model of the issues – but what it does excellently is educate the player as they go.

“Before playing, for instance, I didn’t know that global methane emissions account for about one-third of human-caused warming. But I do now, because the game got me to invest in methane mitigation tech.”

Of course, as cleverly as the game picks its priorities, it has to leave out any number of factors. Investing in reducing global methane emissions, for instance, whether through sanctions or pouring money into alternate tech, would have vast political ramifications.

The limitations of funding for newsgames mean the developers did not have the ability to create, say, a token system for encouraging competition among green tech companies, nor the ability to become a first-person shooter where you have to defend against death squads sent by aggrieved coal and gas conglomerates, as fantastic as that would have been.

Simplicity by design

I recently played Beecarbonize, a climate change-based game that is classed – ominously! – as a ‘survival game’ on Steam. It makes the smart decision to implement a time-based mechanic, in which the investments you make in four categories (industry, ecosystems, people, and science) pay dividends over time.

But since those investments often reduce your ability to invest in other areas, or even increase the emissions your game board is generating, it becomes a challenge to know where to invest your limited number of tokens. The standard difficulty is hard enough: I’m not brave enough to try Hardcore.

But while Beecarbonize rightly puts the fear of god into the player about climate change, it too is an abstraction of the issues, fronted by a cute cartoon bee.

That’s, of course, by design. No developer would ever try to accurately replicate the causes and cures of climate change. It is, after all, threaded throughout every single aspect of society, politics, art… everything.

And that’s the problem with newsgames in general. No issue exists in a vacuum, and any true simulation game would need to be a 1:1 model of our entire world and culture to truly communicate the issue to a player.

But, realistically, that’s not the point of newsgames. They are approximations by design, created as a fun exploration of a complex issue. Instead, as both the Financial Times’ game and Beecarbonize demonstrate, they are an excellent example of solutions journalism: they don’t pretend to have all the answers, but instead aim to create hope that change is possible in the first place.

In that, they are closer to ‘games’ — which by and large are narratives about triumphing over impossible adversity — than ‘news’, which is mostly about how we’re losing the fight. But, because they focus on solutions, they inspire us to approach real-world problems with optimism that they can be solved.