What games get wrong about illness

Very few games explore the reality of being struck down with a sickness

There’s a moment in Batman: Arkham City in which our favourite nocturnal pugilist begins succumbing to an infection. Naturally, this being Gotham, this isn’t just a cold.

To buy himself more time, da Bats seeks out the rejuvenating water of the Lazarus Pits, which can raise the dead and are presumably just a little more effective than a hot Lemsip with ginger and a dash of whisky. Along the way he has to fight automatons, a coterie of ninja women, and the effects of the illness itself.

In practice that just means that he will occasionally disentangle himself from player control to stagger a bit, or to fall to the ground in a cutscene only to climb back to his feet immediately afterwards. His face gets a bit veiny. The effects of being infected have very little bearing on the gameplay, only the narrative.

It’s a shame, though, because other sections in the Arkham series do genuinely play with Batman’s – and therefore the player’s – senses and perception in a way that replicates the symptoms of illnesses. The Mad Hatter and Scarecrow sections play with hallucinogenics and paranoia, in the way that sufferers of Schizoaffective Disorder can experience the world, for example.

But the game could have done more with Batman’s infection – especially as it is such a major story beat.

During the Spanish Flu epidemic (which I will shut up about at some point) sufferers often awoke to find themselves in a muted, almost monochrome world, colour having been leeched from their perception. You know, almost in the way that the box art for the game portrays Batman and Gotham. Perhaps as the infection progressed, almost without the player noticing, the game’s saturation could ratchet right down.

Instead, though, we get the Standard Video Game Infection (SVGI).

SVGI is very easy to diagnose. If your gaming protagonist has any of the following symptoms, it is likely they have contracted it.

Slow and staggering movement, often in short bursts between normal movement

A reduced health and or energy bar as a visual indicator (although you’ll almost never experience an enemy that would make that a genuine danger)

Groaning and or panting, or clutching their side in a new idle animation

The effect passes within a few seconds, short minutes at most

And that’s about it. You can spot this in even very good games like the Arkham series, at the start of Route C of NieR: Automata, in Tomb Raider (2013), Uncharted 3… and those are just the ones I could think of off the top of my head before consulting the Injured Player Stage page on TV Tropes.

In control

It’s understandable why developers would do this. You don’t necessarily want to take control from the player, or remove abilities from them, for too long. But it does limit or mitigate the ravages of illness – and that can diminish the impact of the narrative.

Physical sickness rarely comes and goes swiftly. It incubates, weakens the host, until the time is right for it to bloom and really fuck you up. It is a lengthy battle between your body’s defences (and the whisky-infused Lemsip) and the infection, not a one-round bout. It is something you have to live with, rather than shrug off. It can be debilitating for a long, long time.

That Dragon, Cancer explored this heartbreaking effect, by having nothing the player does have any tangible impact on the suffering of a sick child. Since it was developed by parents who were going through that exact situation, we can safely say it is an accurate representation of that worst case scenario, explored through the medium of gaming.

Many great games deal with a chronic illness in their narratives, and do so very well.

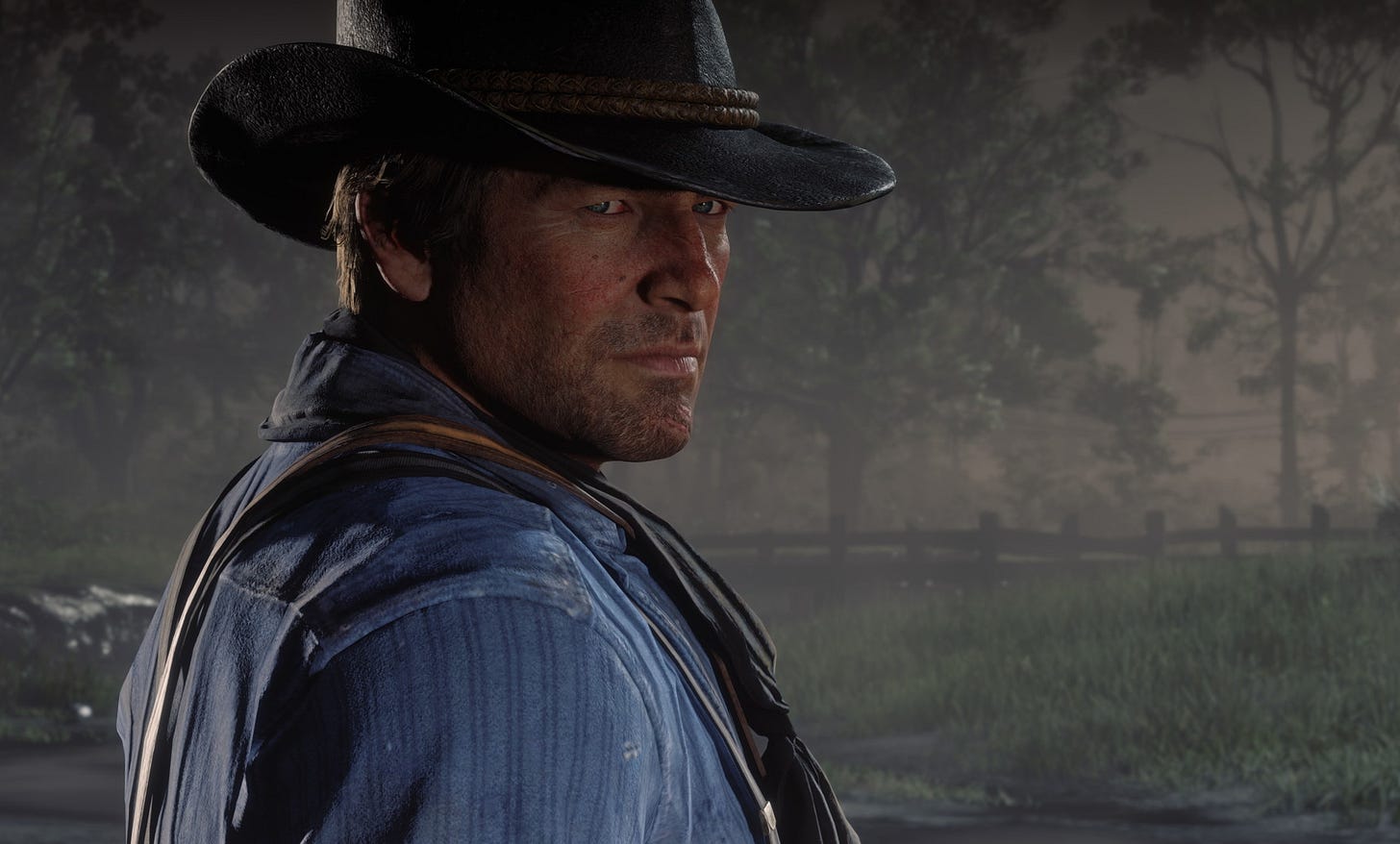

Arthur Morgan’s journey through the latter half of Red Dead Redemption 2 is explicitly about his slow death from TB, and grappling with what legacy he wants to leave. It is reflected in gameplay by an inability to have the player increase his weight, and a handicap in the final battle, but it is mostly a narrative conceit. Silent Hill 2’s backstory and much of its symbolism are based on the protagonist’s wife’s slow deterioration from a wasting illness. But James moves and shoots just fine. Joel gets impaled by a rusty bit of rebar towards the mid-point of The Last of Us and this has a long-lasting impact on the story… but the player then takes control of Ellie.

So in games, you almost never have to play through, experience, the long-term impact of a physical illness or injury. It might be frustrating, yes, but I think it would be an interesting experiment to create a game like that, one that subverts the standard progression of a player character’s growth and plays with the interactivity of the medium.

The road back to health

Bizarrely, one of the best instances of a game actually doing something like this is Majora’s Mask (my beloved). Yep, the one about the moon falling to earth.

At the outset of the adventure, protagonist Link is robbed by the game’s antagonist. After a brief period of gameplay in which Link flips, leaps, rolls, and sprints across a forest floor, he is cursed and forced into the body of a Deku Scrub – a standard Zelda enemy. In this stunted form he can just about waddle, a far cry from the acrobatics he was able to do beforehand. While the new form comes with unique abilities, it is never portrayed as anything other than a weak and limited form in gameplay, rarely able to take on even the lightest challenges in the game.

I think that’s intentional. The game is suffused with sickness as a theme. The Southern Swamp is poisoned, Great Bay’s wildlife is dying. Ikana Canyon is a kingdom of the dead, in which Link can undertake a sidequest to heal a father succumbing to a transformative illness.

And the diegetic name of the song that returns Link to his original form, heals the father, and is instrumental(!) in saving Termina? The Song of Healing. By locking the player character into a weak and debilitated form at the very start of the game, the developers make his own recovery a parallel with that of the land. It’s very Fisher King.

So there are very solid reasons why games don’t accurately reflect the experience of being physically ill. Many do, with mental illnesses, because the player is still, well, playing. In control.

But I can’t help but want to know what it might look like – and whether games as an art form have a responsibility to explore it.

Hello reader, can I ask you a favour? This is the 51st post on this blog — and I have fewer subscribers than I do posts. I would love to keep writing on this topic, but it’s increasingly hard to justify doing that when there’s no growth. If you could, I’d love it if you could share or recommend this post — or any of the other 50 — to help it grow. Thank you in advance!